Perhaps this extraordinary, vivid account will finally prompt more Americans to make the connection. (Yes, this connection):

|

| Joyce McMillan of JMac For Families has a reminder for us. |

A word of advice to any journalist contemplating entering the National Magazine Awards competition in the Reporting category – and I say this with the utmost respect: If you’re not Caitlin Dickerson of The Atlantic, you probably shouldn’t bother. Dickerson’s masterpiece of in-depth reporting on the Trump Administration’s policy of family separation at the Mexican border is that good.

It took 18 months of reporting, more than 150 interviews, and a lawsuit to obtain relevant documents. Yes, it’s nearly 30,000 words – the longest article The Atlantic has published in its 165-year history. But it’s also, to use that awful word from blurbs about thrillers: unputdownable.

You may think you know everything about that ghastly exercise in calculated cruelty. Trust me, you don’t. Dickerson reveals that it was worse than we could have imagined. “It’s been said of other Trump-era projects that the administration’s incompetence mitigated its malevolence,” Dickerson writes. “Here, the opposite happened.”

You may think you’ve heard so much about what happened that you no longer can be shocked or brought to tears. Perhaps. But consider just one of the many “little picture” examples Dickerson cites as she tells the story of this exercise in mass child abuse:

Remember the audio leaked to ProPublica of desperate children crying for their parents at a detention center?

Now consider this from Dickerson’s story, as she describes how, month after month, parents had no idea where their children were:

One woman, Cindy Madrid, only located her 6-year-old daughter, Ximena, after recognizing Ximena’s voice in the audio released by ProPublica, which was played during a news broadcast shown in the South Texas detention center where Madrid was being detained.

But even as this story rekindles feelings of despair over what was done to thousands of children in our name, and fury at those who did it, it also rekindles the frustration a lot of us felt at the time about the failure to make the connection. Any regular reader of this Blog knows which connection.

The very fact that this story reveals so much about the sadistic glee that some in the Trump Administration seemed to take in tearing apart families makes it harder to understand one simple fact: People with only the best of intentions are doing the same thing to hundreds of thousands of children right now.

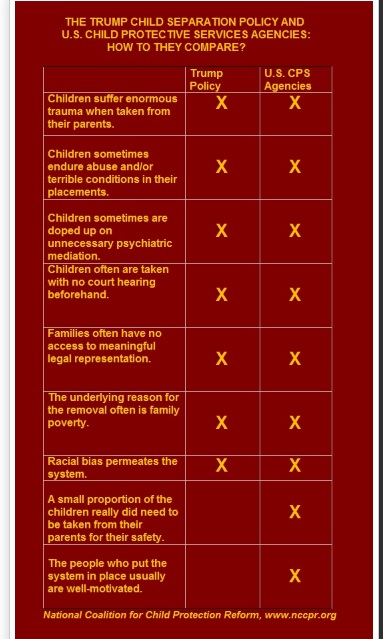

Take almost any example from Dickerson’s story, and there is a comparable example from the American system of what is called “child welfare” – or as it should be called, family policing. Whether the people tearing a child from the arms of a loving parent have an ID that says “Child Protective Services” or one that says “Border Patrol,” the anguish experienced by the children is the same. While Trump’s family separation policy was underway, we even prepared this handy chart comparing how the two systems work:

But we wall ourselves off from that anguish in two ways: First by convincing ourselves it’s somehow different if the people taking the children mean well. But also by demonizing the parents.

More than 50 years of what’s been aptly called “health terrorism” persuaded many Americans that while the parents at the border are innocent victims, the parents who lose their children to CPS agencies all must be beating and torturing their children. A very few of them are. But most have far more in common with impoverished refugees than with those depicted in the horror stories that fuel health terrorism. The Atlantic itself contributed to the demonization of families caught up in the traditional American family policing system in a 2018 story (to which I will not link).

That’s why the same scenes that prompt us to draw back in horror when they play out at the Mexican border make too many of us cheer when they happen in our own backyards. The family police revel in their middle-class rescue fantasies and celebrate – yes, celebrate – when these overwhelmingly poor disproportionately nonwhite families are torn apart forever.

But the children taken by the family police are shedding the same sorts of tears as those taken by the Border Patrol – for the same reasons.

Dickerson’s story also reveals how little those who don’t encounter family policing every day know about how it really works.

At one point, Dickerson cites one of the few people who comes off well in her story, a U.S. Attorney who tried to reunite the families:

He was outraged. In no place in the American criminal-justice system, he reportedly testified, would it be considered either ethically or legally permissible to keep children from their parents for punitive purposes after their legal process is completed. “We wouldn’t do that to a murderer,” much less a parent facing misdemeanor charges …

Wanna bet?

Technically, he’s partly right. But only because family policing is part of the civil, not criminal legal system.

Is it not “keeping children from their parents for punitive purposes” if children are held in foster care even after their parents jump through every hoop the family police agency imposes on them, just because they can’t afford to pay the ransom the agency has imposed? (Agencies don’t use that term, of course, they call it “child support” to reimburse them for the cost of “caring” for the children.) Since it doesn’t help the children and it doesn’t even help the agency – collection efforts cost more than what’s collected – how is this anything but punishment?

And don’t forget all the victims of the “war on drugs” who were released from jail sentences they often never should have had to serve, only to find their children gone – forever – because under the odious Adoption and Safe Families Act, CPS agencies can seek termination of parental rights for no other reason than the passage of a specified amount of time. (This also applies to families detained and/or deported by immigration authorities.)

For more examples of just how much the American family policing system can get away with, see NCCPR's Due Process Agenda.

Similarly, in exposing the horror of the huge institutions in which children taken at the border were warehoused, the story states that:

Large-scale institutions had long since been eliminated from the domestic child-welfare system because they were found to be traumatizing and unsafe.

No, they haven’t. They’ve just rebranded as “residential treatment centers.” And they’ve been engulfed in scandal after scandal, after scandal after scandal.

The worst way to respond to the Atlantic story would be to say: At least an outraged public ultimately was able to put a stop to it. Because the needless separation of families has never stopped. It began long before Donald Trump – in fact, its roots are in slavery – and it continues to this day. So as you read Caitlin Dickerson’s brilliant reporting, keep in mind the reminder from Joyce McMillan of JMac For Families that’s at the top of this post: They separate children at the border of Harlem, too.